Written by Bernie Weisz Historian/Vietnam War Pembroke Pines, Florida May 26, 2010 E Mail Address: BernWei1@aol.com Title of Reivew: "A Vietnam Vet at 63:Recently Realizing what It Means To Want To Live!"

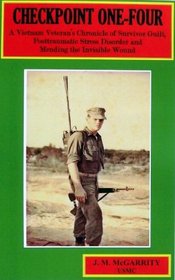

It could easily be called immaturity, poor impulse control, low self esteem, or whatever psychological label you care to affix to sufferers of "Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome" brought on as a consequence of what a Veteran witnessed in their tour of Vietnam from the vantage point of forty years after the final American left S.E. Asia. Certainly, everyone reacts to trauma, disasters, catastrophes and death differently. It is "Monday morning quarterbacking" to say that anyone who lets memories of what happened in Vietnam senselessly and needlessly interfere with a Veteran's future life. P.T.S.D. is real and debilitating. For doubters, simply read James McGarrity's ordeal in "Checkpoint One-Four" and see for yourself if the syndrome is a fictional entity.

Nobody knows how they will react when they see death. When one volunteers or is drafted during wartime, there is a high probability that a soldier, unless designated for rear duty, will see combat and loss of life. There is no telling if the bravest man during basic training will act like a scowling coward or Audie Murphty when the bullets starts flying. In 1966, with the war in S.E. Asia heating up, J.P. McGarrity joined the Marine corps. After graduating from Boot Camp at Paris Island, South Carolina, and Infantry Training at Camp Geiger (Camp Geiger is part of the Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune complex, North Carolina) he reported to California's Camp Pendleton for final embarkation to Vietnam. As was customary for deployment during the Vietnam War, McGarrity flew a commercial jet via Honolulu and Okinawa, with the final destination being Danang, South Vietnam.

Jim McGarrity had a best friend whom he met at radio school in California named Phil. He made it from California and Okinawa to Vietnam with Phil as his companion. McGarrity described his first day in Vietnam vividly, as well as his next trauma, being separated from his last remnant of familiarity, his best friend. Accordingly, he wrote: "Sleep probably isn't the right term for how my first night went in Vietnam. The smells of the world outside the dirty hooch screen were intoxicating; a combination of flowers and burning wood and stale beer;cigarettes and gunpowder;coffee and aftershave;dirty feet and diesel fuel-a lot of diesel fuel. I was glad Phil was still with me and in the morning we went to chow together, anxious about our assignments we'd be getting. Afterward we mustered in front of a small plywood shack, not much bigger than a chicken coop. From there things happened so fast, that before I knew it, Phil was gone and I was alone". Despite the fact that his Military Occupational Specialty was as a radio operator, McGarrity was shipped up to I Corps, Phu Bai, as a member of the "3rd Motor Transport Battalion". Throughout the beginning of "Checkpoint One-Four", McGarrity continually wrote of his fear of responsibility and low self esteem based on complicated issues from his childhood and upbringing. McGarrity's 3rd Motors mission in Vietnam was to deliver cargo, i.e. food and ammunition, and in March of 1967 he found himself a passanger in what was called a "mine truck". He described his job in the following words: "Most of the guys hated it, but I actually enjoyed it. Leading the long line of vehicles gave me a great sense of accomplishment and thankfully, the only incidents we encountered were from occasional light road mines that would blow a wheel or fender off".

In an attempt to bolster his elusive sense of responsibility, McGarrity commented: "Soon I'd be back on the highway myself, heading north to Camp Evans or Dong Ha or Quang Tri or maybe as far as Khe Sanh; delivering the precious cargoes of ammunition and food and clothing and everything imaginable that our fellow Marines in the far off camps and fire bases of I Corps required for their every day survival". With the convoy on it's way to Hue, Jim placed a speaker, which he called a "squawk box" between himself and the driver, to amplify transmissions from his PRC-10 (Portable Radio Communications). Both fearful of driving over land mines planted in the ground by the Viet Cong, Jim thought he heard a garbled communication over the squawk box of a firefight ahead. Accidentally, the speaker fell off the seat between the two, and as the driver reached for it on the cab floor and took his eye off the road, the cab violently overturned.

The driver leaped from the cab, but McGarrity was trapped inside it, neck deep in muddy water. He described his first trauma, something that started his descent into hopeless P.T.S.D. as follows: "Soon, I heard voices around me in the water and I saw several Marines kneeled outside the window, pulling the soaked sandbags off of me. In no time I was free and being dragged up the bank to the road, soaked and filthy, but otherwise not visibly injured. There was a somber mood when I arrived topside. I could see several Marines gathered in a tight circle, looking down at something on the pavement. I expected it to be the driver. but as I moved closer, I was shocked to see our beloved battalion Master Sergeant, broken and twisted, struggling for his last breath, as a jagged bone protruding from his forearm waved at the sun with each exhale. He died right there. And then it hit me. He had been riding in back in the open bed. I didn't know he was there. He hardly ever left the compound. When the truck flipped he must have been thrown off, or jumped. "Oh my God," I said to myself."Is this my fault?" This was the tip of the iceberg. In late summer of 1967, while driving convoys in the Ashau Valley, there were increasing incidents of enemy terrorism. McGarrity wrote about NVA subterfuge: "These were the real bad guys: the NVA, the North Vietnamese Army regulars who operated the miles of underground cities and weapons' caches and dirt-walled surgery rooms lit by coal lanterns. These secret tunnels also accommodated NVA political cadres from North Vietnam who coordinated guerilla activities between local VC and battle-hardened troops of Ho Chi Minh's liberation forces. Road mines were getting more powerful, some blowing our heavy trucks straight up in the air, sending them cart-wheeling end over end. It was a frightening sight as the vehicles landed on their topsides with their drivers inside; artillery rounds scattering onto the road and diesel fuel seeping around us and into the rice paddies and canals. Once, on a section of road into the Ashau Valley as we plowed ankle-deep through an unnaturally deep, red powder;maybe Agent orange, vehicles returning toward us from the valley were exploding within yards of me on the oncoming side". Next, in August, 1967, slightly south of Camp Evans, Thua Thien Province, one of the vehicles in McGarrity's convoy went over a land mine, producing a mass-wounding of his fellow Marines. McGarrity was asked to bring in the Medevac Helicopter by radio to extract the most severely wounded Marines. While the helicopter was hovering close by, McGarrity couldn't seem to raise the chopper over the radio. Unable to establish radio communication with the pilot, McGarrity wrote: "I seemed to be doing everything right. I had a smoke canister ready to throw-there was background noise on the frequency, and I continued to call him. A fellow Marine asked why the chopper above kept hovering without landing. McGarrity exclaimed that he couldn't reach him. Then, with a humiliating blow to his pride and ego, McGarrity was shown that he was using the wrong frequency to contact the chopper. After the chopper finally landed, McGarrity depressingly mused that if the other Marine wasn't there, he wouldn't have ben able to reach the pilot, the chopper might not have landed and the wounded Marines could have died. With great remorse, guilt and chagrin, McGarrity promised himself never to fail, make a mistake nor let his brothers down. However, the worst was yet to come.

In September, 1967, McGarrity was part of a convoy that came upon a bridge that appeared to have some roadwork going on alongside the approaching road. McGarrity stopped his truck and watched some combat engineers check some pyramid shaped piles of gravel. Although no one was hurt, McGarrity witnessed engineers find and disarm communist rockets perfectly positioned to blast his convoy to "kingdom come" if they were not discovered and rendered harmless. Two weeks later, McGarrity was on another convoy, going along Highway 1 towards Hue. As the name of the book is called, the convoy reached "Checkpoint One-Four" just before another bridge. With the memory of the incident from a fortnight ago fresh in mind, McGarrity got out of the passanger side of his parked truck and watched engineers again check for a booby trap around the bridge they were to cross. Out of nowhere, an old man came out from under the bridge and started mysteriously running away. McGarrity wrote as follows: "In my mind, only one thing was clear-he almost got caught hiding a mine or a detonator and he was trying to escape. I drew my .45 and led the old man like a hunter with game on the run. I had absolutely no thought of the consequences; no moral compass;no compassion or logic for what I was about to do. I had decided in an instant that I would kill him, and that would be all there was to it. Then, out of nowhere, a convoy commander grabbed McGarrity's wrist a second before he was to fire his weapon, exclaiming: "You just can't shoot unarmed civilians!" And then the officer stomped off, plopping himself down in the passenger seat of the jeep. No bomb was found, McGarrity was humiliated, the "Papa San" made off unscathed, and the convoy continued without incident.

Next, the defining moment in Jim McGarrity's life would occur in October, 1967. This event would precipitate a lifelong battle with it's horrible memory and concomitant P.T.S.D. Permanently etched in his hippocampus, the memory storing organ of one's brain, this occurrence would also activate and overwhelm another part of the human psyche, the amygdala. Although I didn't entirely understand this concept, McGarrity elucidated that a human's amygdala doesn't process facts. It only prepares a human for "fight or flight". What happens when a soldier's brain is overwhelmed, seeing extreme horror or death? McGarrity explained the result like this: "The result can be a "burned-in" recollection of the event as the hippocampus is saturated and parts of it "drowns" damaging memories based on logic with those of the horror or death; the abandonment and guilt; the fear of insanity and the helplessness of betrayal. This is where forever after, those of us with P.T.S.D. will act irrationally during moments in which our brains can only recognize a fight or flight situation. Like preparing to kill or be killed at the sound of a snapping twig. This is what happened to me on an October morning in 1967, when our convoy was ambushed on a desolate stretch of highway in the northern-most section of South Vietnam".

What could have happened that was so devastating? I have spoken to Bobby Briscoe, author of the book "Jungle Warriors". He explained to me the trauma of himself being the only survivor of an ambushed 6 man L.R.R.P. team, with the only body part remaining of his fellow team members was one man's chest cavity. There is Robert Topmiller's description in "Red Clay On My Boots" whereupon he vividly wrote about the horrors he witnessed as a medic at Khe Sanh during the January, 1968 Tet Offensive. Did Topmiller ever recover? It just so happens that he was buried last year, the victim of a self inflicted gunshot wound in his mouth. A Chinook pilot, Bruce Lake, described transporting from the battlefield decaying bodies of dozens of U.S. soldiers. In "1500 feet Over Vietnam", Lake wrote that the smell of death was so horrifying that he had to keep a piece of "Wrigley's Juicy Fruit Gum" under his nose to tolerate it. Has he ever mentally recovered form this? Jim McGarrity's ordeal was equally traumatizing, if not the most horrifying I have ever read.

Early October, 1967. Just north of Hue, McGarrity was a passenger in a convoy that stopped short of a bridge once again. Halting at a checkpoint, the driver of McGarrity's vehicle pulled up just short of the approaching bridge and got out to stretch his legs. McGarrity sat in the cab of the truck and relaxed as he smoked a cigarette. Having a clear view of the convoy commander in his jeep, McGarrity wondered if he should warn him of the rockets found back in September. After careful consideration, McGarrity thought to hell with this convoy commander, letting him become a hero with someone else's help. That was the last conscious thought McGarrity had before his world would be permanently turned upside down. It is best to let McGarrity's words describe the following: "In an instant, everything I understood and believed in was vaporized as a wave of air swept over my right arm, followed by a sound that any narrative I could offer would be an injustice".

Thrown from the truck in the blast, McGarrity continued: "Instinctively I grabbed my radio and jumped, or was ejected out the door, where I landed in a shallow swale in the grass. I reached over my shoulder with my right hand and rolled the two pre-set dials to the MEDEVAC frequency. Realizing that I had lived, sounds, at first like buzzing alerted my senses. The inhumanity of the injuries that began to unfold was staggering. A Marine had been decapitated, and looking at his face I got the impression it was still conscious and surprised. The head seemed to be looking at it's own body lying a few yards away and thinking: "That can't be me-I'm right here". McGarrity continued: "Not far from the startled head, another Marine was sitting on a log, holding one foot with both hands, wondering where his toes had gone, while 10 yards from him, Pappy, a well-liked and popular driver who had served in Korea and reenlisted to serve in Vietnam was on his back, burnt to a crisp-both arms frozen upwards to heaven, as if he were calling the angels to take him home".

With smoke coming from Pappy's charred remains, McGarrity stared at his corpse and explained his thought processes: "I knew there would be a full can of water strapped to the rear of the lead jeep, so I figured if I poured water on Pappy he'd stop smoldering and I could cover him with something. Purely out of courtesy, as now I was seeing us all as victims, I thought I'd tell the CO my intentions". This officer was the same one who prevented McGarrity from taking a shot at the old man by the bridge that past September. After McGarrity asked this CO if he could pour water on Pappy to stop him from smoldering, this formerly admonishing officer just sat there catatonically frozen, unable to answer. McGarrity did pour water on Pappy, and then covered his corpse. As he did this, he felt extreme pity towards this officer. McGarrity saw Marines that were legless, bleeding, and crying for their mothers. To this, he wrote: "Everything was clear now; the sounds, the smells, the color of the grass, the feel of the air, the odor of blood, like the smell in my cousin's basement where we skinned muskrats".

Then, McGarrity walked by a small and immobilized tracked vehicle called an "Ontos", and was asked by a Marine to help get the body of one of the wounded down to the ground. McGarrity continued: "I reached out with both arms and prepared to receive the body of whom most likely had been the Ontos' operator standing in the driver's hole, exposed when the blast occurred. I put my right arm under his neck as his upper body descended; bracing myself for the expectation of a person's full weight. But instead, as he flopped into my arms, it was as if a child had been delivered to me, as nothing but his bottom torso from the pelvis down rested in my left hand, and the upper-half of his body with the flak jacket wiggled it's way onto my right hand. All that was connecting his two halves together was his flesh-stripped spine; red and bumpy, like a grotesque slinky-toy tapping slightly at my belt line."

McGarrity carried the dead Marine in his arms a few feet, and was warned to watch where he walked, as he could possibly step on a NVA land mine and cause more horror. McGarrity next wrote a chilling passage, a small iota that caused a lifetime of guilt: "I seemed to be getting weaker with each step, and when I reached the edge of the road I let the dead Marine slip from my arms. He folded into a twisted heap at my feet like a broken puppet. I remember feeling that I might go insane; that something was changing in me with each step. For a moment I seemed to be aware of what crazy people must feel like and it scared the hell out of me to think that I might be seconds away from what some describe as a person "snapping". McGarrity's thoughts after this became muddled. He wrote that he saw the old man that he shot at back in September and decided once again to kill him. but before McGarrity could do this, allegedly everything went "blank".

Obviously in shock, McGarrity vaguely recalled unloading bodies from a field ambulance, possibly at Phu Bai. The rest was a blur. He rotated back to the U.S. in April, 1968, right after the April 4th assassination of Martin Luther King by James Earl Ray in Memphis, Tennessee. His hometown of Akron, Ohio was under curfew, due to riots as a reaction to the King killing. McGarrity lapsed into a life of drugs, alcohol and isolation, a psychological recluse captive of the pervasive effects of P.T.S.D. However, there is a positive message in the final pages of this excellent book. Through "Checkpoint One-Four" Jim McGarrity teaches the reader that P.T.S.D can never be cured, but rather mended with daily vigilance. McGarrity diligently explains the causes, effects, and the curative therapy. He also writes of his eventual discovery of happiness, enjoying a wonderful and supportive wife, sister and loving son and daughter, and a zest for life that before his first-ever visit to a Veteran's Administration health clinic in 2004 never existed.. What is it like to be affected by P.T.S.D.? In Terry Rizzuti's book "The Second Tour" there is a passage where the protagonist, severely afflicted by this debilitating condition, is trying to describe to his wife what being in Vietnam was like. Rizzuti wrote the following: "I opened my mouth to yell, to tell her what Vietnam was like, but no sound came out, only a tremble and then a tear and then several tears and then convulsions followed by silence and that haunting single thought I'm alone again, I'll always be alone." Regardless, this book is not all "doom and Gloom". As Jim mcGarrity attempts to offer, by actively participating in therapy, pathways to hope will emerge. Consequently. the nightmares, anger, depression and hopelessness can be put in proper perspective and a better life is possible. This book is an absolute must for any VA hospital, Veteran or family member of one, or for that matter ANYONE trying to comprehend Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome regardless of it's causes.

It could easily be called immaturity, poor impulse control, low self esteem, or whatever psychological label you care to affix to sufferers of "Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome" brought on as a consequence of what a Veteran witnessed in their tour of Vietnam from the vantage point of forty years after the final American left S.E. Asia. Certainly, everyone reacts to trauma, disasters, catastrophes and death differently. It is "Monday morning quarterbacking" to say that anyone who lets memories of what happened in Vietnam senselessly and needlessly interfere with a Veteran's future life. P.T.S.D. is real and debilitating. For doubters, simply read James McGarrity's ordeal in "Checkpoint One-Four" and see for yourself if the syndrome is a fictional entity.

Nobody knows how they will react when they see death. When one volunteers or is drafted during wartime, there is a high probability that a soldier, unless designated for rear duty, will see combat and loss of life. There is no telling if the bravest man during basic training will act like a scowling coward or Audie Murphty when the bullets starts flying. In 1966, with the war in S.E. Asia heating up, J.P. McGarrity joined the Marine corps. After graduating from Boot Camp at Paris Island, South Carolina, and Infantry Training at Camp Geiger (Camp Geiger is part of the Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune complex, North Carolina) he reported to California's Camp Pendleton for final embarkation to Vietnam. As was customary for deployment during the Vietnam War, McGarrity flew a commercial jet via Honolulu and Okinawa, with the final destination being Danang, South Vietnam.

Jim McGarrity had a best friend whom he met at radio school in California named Phil. He made it from California and Okinawa to Vietnam with Phil as his companion. McGarrity described his first day in Vietnam vividly, as well as his next trauma, being separated from his last remnant of familiarity, his best friend. Accordingly, he wrote: "Sleep probably isn't the right term for how my first night went in Vietnam. The smells of the world outside the dirty hooch screen were intoxicating; a combination of flowers and burning wood and stale beer;cigarettes and gunpowder;coffee and aftershave;dirty feet and diesel fuel-a lot of diesel fuel. I was glad Phil was still with me and in the morning we went to chow together, anxious about our assignments we'd be getting. Afterward we mustered in front of a small plywood shack, not much bigger than a chicken coop. From there things happened so fast, that before I knew it, Phil was gone and I was alone". Despite the fact that his Military Occupational Specialty was as a radio operator, McGarrity was shipped up to I Corps, Phu Bai, as a member of the "3rd Motor Transport Battalion". Throughout the beginning of "Checkpoint One-Four", McGarrity continually wrote of his fear of responsibility and low self esteem based on complicated issues from his childhood and upbringing. McGarrity's 3rd Motors mission in Vietnam was to deliver cargo, i.e. food and ammunition, and in March of 1967 he found himself a passanger in what was called a "mine truck". He described his job in the following words: "Most of the guys hated it, but I actually enjoyed it. Leading the long line of vehicles gave me a great sense of accomplishment and thankfully, the only incidents we encountered were from occasional light road mines that would blow a wheel or fender off".

In an attempt to bolster his elusive sense of responsibility, McGarrity commented: "Soon I'd be back on the highway myself, heading north to Camp Evans or Dong Ha or Quang Tri or maybe as far as Khe Sanh; delivering the precious cargoes of ammunition and food and clothing and everything imaginable that our fellow Marines in the far off camps and fire bases of I Corps required for their every day survival". With the convoy on it's way to Hue, Jim placed a speaker, which he called a "squawk box" between himself and the driver, to amplify transmissions from his PRC-10 (Portable Radio Communications). Both fearful of driving over land mines planted in the ground by the Viet Cong, Jim thought he heard a garbled communication over the squawk box of a firefight ahead. Accidentally, the speaker fell off the seat between the two, and as the driver reached for it on the cab floor and took his eye off the road, the cab violently overturned.

The driver leaped from the cab, but McGarrity was trapped inside it, neck deep in muddy water. He described his first trauma, something that started his descent into hopeless P.T.S.D. as follows: "Soon, I heard voices around me in the water and I saw several Marines kneeled outside the window, pulling the soaked sandbags off of me. In no time I was free and being dragged up the bank to the road, soaked and filthy, but otherwise not visibly injured. There was a somber mood when I arrived topside. I could see several Marines gathered in a tight circle, looking down at something on the pavement. I expected it to be the driver. but as I moved closer, I was shocked to see our beloved battalion Master Sergeant, broken and twisted, struggling for his last breath, as a jagged bone protruding from his forearm waved at the sun with each exhale. He died right there. And then it hit me. He had been riding in back in the open bed. I didn't know he was there. He hardly ever left the compound. When the truck flipped he must have been thrown off, or jumped. "Oh my God," I said to myself."Is this my fault?" This was the tip of the iceberg. In late summer of 1967, while driving convoys in the Ashau Valley, there were increasing incidents of enemy terrorism. McGarrity wrote about NVA subterfuge: "These were the real bad guys: the NVA, the North Vietnamese Army regulars who operated the miles of underground cities and weapons' caches and dirt-walled surgery rooms lit by coal lanterns. These secret tunnels also accommodated NVA political cadres from North Vietnam who coordinated guerilla activities between local VC and battle-hardened troops of Ho Chi Minh's liberation forces. Road mines were getting more powerful, some blowing our heavy trucks straight up in the air, sending them cart-wheeling end over end. It was a frightening sight as the vehicles landed on their topsides with their drivers inside; artillery rounds scattering onto the road and diesel fuel seeping around us and into the rice paddies and canals. Once, on a section of road into the Ashau Valley as we plowed ankle-deep through an unnaturally deep, red powder;maybe Agent orange, vehicles returning toward us from the valley were exploding within yards of me on the oncoming side". Next, in August, 1967, slightly south of Camp Evans, Thua Thien Province, one of the vehicles in McGarrity's convoy went over a land mine, producing a mass-wounding of his fellow Marines. McGarrity was asked to bring in the Medevac Helicopter by radio to extract the most severely wounded Marines. While the helicopter was hovering close by, McGarrity couldn't seem to raise the chopper over the radio. Unable to establish radio communication with the pilot, McGarrity wrote: "I seemed to be doing everything right. I had a smoke canister ready to throw-there was background noise on the frequency, and I continued to call him. A fellow Marine asked why the chopper above kept hovering without landing. McGarrity exclaimed that he couldn't reach him. Then, with a humiliating blow to his pride and ego, McGarrity was shown that he was using the wrong frequency to contact the chopper. After the chopper finally landed, McGarrity depressingly mused that if the other Marine wasn't there, he wouldn't have ben able to reach the pilot, the chopper might not have landed and the wounded Marines could have died. With great remorse, guilt and chagrin, McGarrity promised himself never to fail, make a mistake nor let his brothers down. However, the worst was yet to come.

In September, 1967, McGarrity was part of a convoy that came upon a bridge that appeared to have some roadwork going on alongside the approaching road. McGarrity stopped his truck and watched some combat engineers check some pyramid shaped piles of gravel. Although no one was hurt, McGarrity witnessed engineers find and disarm communist rockets perfectly positioned to blast his convoy to "kingdom come" if they were not discovered and rendered harmless. Two weeks later, McGarrity was on another convoy, going along Highway 1 towards Hue. As the name of the book is called, the convoy reached "Checkpoint One-Four" just before another bridge. With the memory of the incident from a fortnight ago fresh in mind, McGarrity got out of the passanger side of his parked truck and watched engineers again check for a booby trap around the bridge they were to cross. Out of nowhere, an old man came out from under the bridge and started mysteriously running away. McGarrity wrote as follows: "In my mind, only one thing was clear-he almost got caught hiding a mine or a detonator and he was trying to escape. I drew my .45 and led the old man like a hunter with game on the run. I had absolutely no thought of the consequences; no moral compass;no compassion or logic for what I was about to do. I had decided in an instant that I would kill him, and that would be all there was to it. Then, out of nowhere, a convoy commander grabbed McGarrity's wrist a second before he was to fire his weapon, exclaiming: "You just can't shoot unarmed civilians!" And then the officer stomped off, plopping himself down in the passenger seat of the jeep. No bomb was found, McGarrity was humiliated, the "Papa San" made off unscathed, and the convoy continued without incident.

Next, the defining moment in Jim McGarrity's life would occur in October, 1967. This event would precipitate a lifelong battle with it's horrible memory and concomitant P.T.S.D. Permanently etched in his hippocampus, the memory storing organ of one's brain, this occurrence would also activate and overwhelm another part of the human psyche, the amygdala. Although I didn't entirely understand this concept, McGarrity elucidated that a human's amygdala doesn't process facts. It only prepares a human for "fight or flight". What happens when a soldier's brain is overwhelmed, seeing extreme horror or death? McGarrity explained the result like this: "The result can be a "burned-in" recollection of the event as the hippocampus is saturated and parts of it "drowns" damaging memories based on logic with those of the horror or death; the abandonment and guilt; the fear of insanity and the helplessness of betrayal. This is where forever after, those of us with P.T.S.D. will act irrationally during moments in which our brains can only recognize a fight or flight situation. Like preparing to kill or be killed at the sound of a snapping twig. This is what happened to me on an October morning in 1967, when our convoy was ambushed on a desolate stretch of highway in the northern-most section of South Vietnam".

What could have happened that was so devastating? I have spoken to Bobby Briscoe, author of the book "Jungle Warriors". He explained to me the trauma of himself being the only survivor of an ambushed 6 man L.R.R.P. team, with the only body part remaining of his fellow team members was one man's chest cavity. There is Robert Topmiller's description in "Red Clay On My Boots" whereupon he vividly wrote about the horrors he witnessed as a medic at Khe Sanh during the January, 1968 Tet Offensive. Did Topmiller ever recover? It just so happens that he was buried last year, the victim of a self inflicted gunshot wound in his mouth. A Chinook pilot, Bruce Lake, described transporting from the battlefield decaying bodies of dozens of U.S. soldiers. In "1500 feet Over Vietnam", Lake wrote that the smell of death was so horrifying that he had to keep a piece of "Wrigley's Juicy Fruit Gum" under his nose to tolerate it. Has he ever mentally recovered form this? Jim McGarrity's ordeal was equally traumatizing, if not the most horrifying I have ever read.

Early October, 1967. Just north of Hue, McGarrity was a passenger in a convoy that stopped short of a bridge once again. Halting at a checkpoint, the driver of McGarrity's vehicle pulled up just short of the approaching bridge and got out to stretch his legs. McGarrity sat in the cab of the truck and relaxed as he smoked a cigarette. Having a clear view of the convoy commander in his jeep, McGarrity wondered if he should warn him of the rockets found back in September. After careful consideration, McGarrity thought to hell with this convoy commander, letting him become a hero with someone else's help. That was the last conscious thought McGarrity had before his world would be permanently turned upside down. It is best to let McGarrity's words describe the following: "In an instant, everything I understood and believed in was vaporized as a wave of air swept over my right arm, followed by a sound that any narrative I could offer would be an injustice".

Thrown from the truck in the blast, McGarrity continued: "Instinctively I grabbed my radio and jumped, or was ejected out the door, where I landed in a shallow swale in the grass. I reached over my shoulder with my right hand and rolled the two pre-set dials to the MEDEVAC frequency. Realizing that I had lived, sounds, at first like buzzing alerted my senses. The inhumanity of the injuries that began to unfold was staggering. A Marine had been decapitated, and looking at his face I got the impression it was still conscious and surprised. The head seemed to be looking at it's own body lying a few yards away and thinking: "That can't be me-I'm right here". McGarrity continued: "Not far from the startled head, another Marine was sitting on a log, holding one foot with both hands, wondering where his toes had gone, while 10 yards from him, Pappy, a well-liked and popular driver who had served in Korea and reenlisted to serve in Vietnam was on his back, burnt to a crisp-both arms frozen upwards to heaven, as if he were calling the angels to take him home".

With smoke coming from Pappy's charred remains, McGarrity stared at his corpse and explained his thought processes: "I knew there would be a full can of water strapped to the rear of the lead jeep, so I figured if I poured water on Pappy he'd stop smoldering and I could cover him with something. Purely out of courtesy, as now I was seeing us all as victims, I thought I'd tell the CO my intentions". This officer was the same one who prevented McGarrity from taking a shot at the old man by the bridge that past September. After McGarrity asked this CO if he could pour water on Pappy to stop him from smoldering, this formerly admonishing officer just sat there catatonically frozen, unable to answer. McGarrity did pour water on Pappy, and then covered his corpse. As he did this, he felt extreme pity towards this officer. McGarrity saw Marines that were legless, bleeding, and crying for their mothers. To this, he wrote: "Everything was clear now; the sounds, the smells, the color of the grass, the feel of the air, the odor of blood, like the smell in my cousin's basement where we skinned muskrats".

Then, McGarrity walked by a small and immobilized tracked vehicle called an "Ontos", and was asked by a Marine to help get the body of one of the wounded down to the ground. McGarrity continued: "I reached out with both arms and prepared to receive the body of whom most likely had been the Ontos' operator standing in the driver's hole, exposed when the blast occurred. I put my right arm under his neck as his upper body descended; bracing myself for the expectation of a person's full weight. But instead, as he flopped into my arms, it was as if a child had been delivered to me, as nothing but his bottom torso from the pelvis down rested in my left hand, and the upper-half of his body with the flak jacket wiggled it's way onto my right hand. All that was connecting his two halves together was his flesh-stripped spine; red and bumpy, like a grotesque slinky-toy tapping slightly at my belt line."

McGarrity carried the dead Marine in his arms a few feet, and was warned to watch where he walked, as he could possibly step on a NVA land mine and cause more horror. McGarrity next wrote a chilling passage, a small iota that caused a lifetime of guilt: "I seemed to be getting weaker with each step, and when I reached the edge of the road I let the dead Marine slip from my arms. He folded into a twisted heap at my feet like a broken puppet. I remember feeling that I might go insane; that something was changing in me with each step. For a moment I seemed to be aware of what crazy people must feel like and it scared the hell out of me to think that I might be seconds away from what some describe as a person "snapping". McGarrity's thoughts after this became muddled. He wrote that he saw the old man that he shot at back in September and decided once again to kill him. but before McGarrity could do this, allegedly everything went "blank".

Obviously in shock, McGarrity vaguely recalled unloading bodies from a field ambulance, possibly at Phu Bai. The rest was a blur. He rotated back to the U.S. in April, 1968, right after the April 4th assassination of Martin Luther King by James Earl Ray in Memphis, Tennessee. His hometown of Akron, Ohio was under curfew, due to riots as a reaction to the King killing. McGarrity lapsed into a life of drugs, alcohol and isolation, a psychological recluse captive of the pervasive effects of P.T.S.D. However, there is a positive message in the final pages of this excellent book. Through "Checkpoint One-Four" Jim McGarrity teaches the reader that P.T.S.D can never be cured, but rather mended with daily vigilance. McGarrity diligently explains the causes, effects, and the curative therapy. He also writes of his eventual discovery of happiness, enjoying a wonderful and supportive wife, sister and loving son and daughter, and a zest for life that before his first-ever visit to a Veteran's Administration health clinic in 2004 never existed.. What is it like to be affected by P.T.S.D.? In Terry Rizzuti's book "The Second Tour" there is a passage where the protagonist, severely afflicted by this debilitating condition, is trying to describe to his wife what being in Vietnam was like. Rizzuti wrote the following: "I opened my mouth to yell, to tell her what Vietnam was like, but no sound came out, only a tremble and then a tear and then several tears and then convulsions followed by silence and that haunting single thought I'm alone again, I'll always be alone." Regardless, this book is not all "doom and Gloom". As Jim mcGarrity attempts to offer, by actively participating in therapy, pathways to hope will emerge. Consequently. the nightmares, anger, depression and hopelessness can be put in proper perspective and a better life is possible. This book is an absolute must for any VA hospital, Veteran or family member of one, or for that matter ANYONE trying to comprehend Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome regardless of it's causes.