When I was in grad school, one of my favorite books on my ancient environmental history reading list was "The First Fossil Hunters," by Adrienne Mayor, which discusses the origins of the many ancient stories and legends which sprang from the discovery of prehistoric fossils of animals extinct for tens of millions of years or more. Those same discoveries would also spark the imaginations of the nineteenth-century figures described in this interesting addition in the Landmark book series.

Both the Greeks and Romans knew that some species of giant creatures once inhabited the areas in which they lived. Many people are at least familiar with the theory that Homer's cyclops supposedly originated from the discovery of elephant skulls, with the single giant hole in the center which resembled an eye socket (it's actually where the trunk is situated), but there are many other mythological stories which were inspired by what ancient peoples found. The griffin, for example, was supposedly first conceived by Scythian miners who found the remains of the "ceratops" family of dinos in the Gobi Desert, but centaurs and other creatures likely had their origins in ancient remains as well.

It's well-known that, as described in the book regarding Native American peoples, the ancients also believed that the often-giant bones they accidentally uncovered were sacred. They frequently collected and deposited impressive collections in temples and even the ancient predecessors of what we could consider museums. Some even attempted to reconstruct the appearance of the prehistoric animals they found, with mixed results.

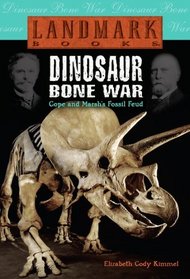

The point here: ancient extinct animals have long been a source of endless fascination for humankind, but only really in the nineteenth century did people make a concerted effort to apply scientific methods to studying them. This short volume, in true Landmark style, focuses as much on the personal stories of the individuals involved as the subject matter, here in the form of two rival scientists (and a third peripheral one), Othniel Charles (O.C.) Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.

Although their backgrounds may have differed somewhat, both developed an almost singular obsession with discovering new species of prehistoric creatures... and with outdoing the other. The two former acquaintances, if not friends, engaged in some almost comical one-upsmanship to become the per-eminent "paleontologist" in the United States, which was an almost entirely new field, which had essentially been founded a generation prior by illustrious predecessor Joseph Leidy, who is widely considered to be the Father of Paleontology.

Marsh was the son of a poor farmer, whose mother died when he was only three years old, so his prospects seemed somewhat bleak. He soon discovered that he had a wealthy uncle, none other than George Peabody (i.e., Yale University's Peabody Museum of Natural History, which was eventually named for him), who funded much of Marsh's education and early efforts in the mid-nineteenth century. He was able to attend graduate school at Yale, and then in Germany, where the real research was going on in the field of paleontology.

Cope, about ten years his junior, was born to a more wealthy family and naturally excelled at natural history. He studied at the prestigious Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, publishing his first scholarly article at age 18. He likewise went to Germany to study under the field's early luminaries, where he actually met O.C. Marsh. It is perhaps fortunate that they did: both were of fighting age during the US Civil War, and their academic pursuits overseas may have resulted in both of them avoiding the draft.

The two reportedly maintained at least an amicable relationship, even upon returning to the US, but that wasn't to last. Marsh reportedly seriously undercut Cope by making a deal with one of Cope's suppliers, which the book talks about, and things just deteriorated from there.

I don't want to rehash the whole soap opera, but things escalated to the point that the two were taking such childish pot shots at each other that first, scientific journals refused to publish their tit-for-tat attacks on each other's work, and, then, when things got worse and Cope went to the press, when Marsh undercut his ability to publish a second volume of what was essentially Cope's life's work, even the newspapers eventually stopped publishing their attacks on each other.

Much of their personal vendetta against each other, which had involved employing spies who kept each other in the loop about the other's work and the location of secret bone caches, to even destroying priceless fossils to prevent their rival from obtaining them, somewhat surprisingly, was halted when surprisingly, the US government stepped in at long last. It essentially put an end to the childish antics, and silenced both of them with the dissolution of Marsh's government position, which even forced him to relinquish some of his private collection on account of claims that the remains had been found on government land and were thus essentially government property. Both then seemingly retreated into their respective spheres to get down to the work of analysis to the end of their days, with both dying within two years of each other, at the dawn of the 20th century.

There are two ways to look at this situation, I suppose: one is to see the glass as half full, in that the fierce competition between the two certainly spurred a more fevered effort than would have naturally arisen otherwise, and so much more was probably produced in a shorter time than if they had been working together. However, the other side of both were rushed and careless (the most egregious example was when Cope placed the head of the mosasaurus on its tail instead of the head, a mistake Marsh corrected and would never let him live down).

Notwithstanding their personal rivalries (and, ironically, when discussing the history of paleontology, the two are almost always discussed together, so even in death their legacies are irrevocably intertwined, whether they like it or not!), they are obviously major figures in the field, and each made invaluable contributions which formed the foundation of paleontology and natural science as we know it today.

Both the Greeks and Romans knew that some species of giant creatures once inhabited the areas in which they lived. Many people are at least familiar with the theory that Homer's cyclops supposedly originated from the discovery of elephant skulls, with the single giant hole in the center which resembled an eye socket (it's actually where the trunk is situated), but there are many other mythological stories which were inspired by what ancient peoples found. The griffin, for example, was supposedly first conceived by Scythian miners who found the remains of the "ceratops" family of dinos in the Gobi Desert, but centaurs and other creatures likely had their origins in ancient remains as well.

It's well-known that, as described in the book regarding Native American peoples, the ancients also believed that the often-giant bones they accidentally uncovered were sacred. They frequently collected and deposited impressive collections in temples and even the ancient predecessors of what we could consider museums. Some even attempted to reconstruct the appearance of the prehistoric animals they found, with mixed results.

The point here: ancient extinct animals have long been a source of endless fascination for humankind, but only really in the nineteenth century did people make a concerted effort to apply scientific methods to studying them. This short volume, in true Landmark style, focuses as much on the personal stories of the individuals involved as the subject matter, here in the form of two rival scientists (and a third peripheral one), Othniel Charles (O.C.) Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.

Although their backgrounds may have differed somewhat, both developed an almost singular obsession with discovering new species of prehistoric creatures... and with outdoing the other. The two former acquaintances, if not friends, engaged in some almost comical one-upsmanship to become the per-eminent "paleontologist" in the United States, which was an almost entirely new field, which had essentially been founded a generation prior by illustrious predecessor Joseph Leidy, who is widely considered to be the Father of Paleontology.

Marsh was the son of a poor farmer, whose mother died when he was only three years old, so his prospects seemed somewhat bleak. He soon discovered that he had a wealthy uncle, none other than George Peabody (i.e., Yale University's Peabody Museum of Natural History, which was eventually named for him), who funded much of Marsh's education and early efforts in the mid-nineteenth century. He was able to attend graduate school at Yale, and then in Germany, where the real research was going on in the field of paleontology.

Cope, about ten years his junior, was born to a more wealthy family and naturally excelled at natural history. He studied at the prestigious Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, publishing his first scholarly article at age 18. He likewise went to Germany to study under the field's early luminaries, where he actually met O.C. Marsh. It is perhaps fortunate that they did: both were of fighting age during the US Civil War, and their academic pursuits overseas may have resulted in both of them avoiding the draft.

The two reportedly maintained at least an amicable relationship, even upon returning to the US, but that wasn't to last. Marsh reportedly seriously undercut Cope by making a deal with one of Cope's suppliers, which the book talks about, and things just deteriorated from there.

I don't want to rehash the whole soap opera, but things escalated to the point that the two were taking such childish pot shots at each other that first, scientific journals refused to publish their tit-for-tat attacks on each other's work, and, then, when things got worse and Cope went to the press, when Marsh undercut his ability to publish a second volume of what was essentially Cope's life's work, even the newspapers eventually stopped publishing their attacks on each other.

Much of their personal vendetta against each other, which had involved employing spies who kept each other in the loop about the other's work and the location of secret bone caches, to even destroying priceless fossils to prevent their rival from obtaining them, somewhat surprisingly, was halted when surprisingly, the US government stepped in at long last. It essentially put an end to the childish antics, and silenced both of them with the dissolution of Marsh's government position, which even forced him to relinquish some of his private collection on account of claims that the remains had been found on government land and were thus essentially government property. Both then seemingly retreated into their respective spheres to get down to the work of analysis to the end of their days, with both dying within two years of each other, at the dawn of the 20th century.

There are two ways to look at this situation, I suppose: one is to see the glass as half full, in that the fierce competition between the two certainly spurred a more fevered effort than would have naturally arisen otherwise, and so much more was probably produced in a shorter time than if they had been working together. However, the other side of both were rushed and careless (the most egregious example was when Cope placed the head of the mosasaurus on its tail instead of the head, a mistake Marsh corrected and would never let him live down).

Notwithstanding their personal rivalries (and, ironically, when discussing the history of paleontology, the two are almost always discussed together, so even in death their legacies are irrevocably intertwined, whether they like it or not!), they are obviously major figures in the field, and each made invaluable contributions which formed the foundation of paleontology and natural science as we know it today.